Training with phishing email examples

Phishing remains one of the most effective initial attack vectors, with individual phishing-related breaches now costing organizations an average of $4.88 million according to IBM's 2024 Cost of a Data Breach Report. These social engineering attacks succeed by exploiting human psychology—curiosity, urgency, trust, fear—making them far more difficult to defend against than technical vulnerabilities.

Security awareness training (SAT) reduces phishing risk by teaching employees to recognize and report suspicious messages. Effective training must go beyond generic warnings to demonstrate real-world examples across different phishing tactics, communication channels, and threat scenarios.

This chapter presents eight phishing examples your training program should include. For each example, we'll examine the attack characteristics, explain the attacker's objective, and demonstrate basic analysis techniques using free online tools.

Summary of key phishing email examples for training concepts

The table below lists the eight different phishing email examples for training that we will present in this article.

| Phishing example |

Description |

|

Unknown sender

|

The "From" email header (visible by the recipient) is random and unknown to the recipient.

|

| Forged sender (a.k.a. email impersonation) |

The "Mail From" email header (invisible to the recipient) is fake and does not match the "From" header. |

| Compromised sender |

Attackers often compromise computers (e.g., Emotet) or email addresses and abuse them to send malicious emails to different email addresses the victim has exchanged emails with. |

| Malicious attachment |

While URL phishing is the most common type, attackers also use attachments with URLs (or malware) to achieve the same result. |

| Malicious QR code |

A relatively new form of phishing email includes a QR code (Quishing) instead of a URL to bypass email security tool scans, which cannot extract the URL from the QR code. |

| Spear phishing |

Unlike other phishing forms, spear phishing is more targeted and does not necessarily start with a link or attachment. |

| Smishing (SMS-phishing) |

SMS-based phishing is a form of phishing that spreads via malicious SMS messages. |

| Vishing (voice-phishing) |

Phone-based phishing is another form of phishing that is gaining popularity, especially for companies exposing phone numbers (e.g., for support or sales) to the internet. |

Eight phishing email examples for training

The eight phishing email examples for training below provide a strong foundation for security awareness training that can reduce the risk of a phishing-based breach.

EXAMPLE 1

Unknown Sender

The most obvious type of phishing email is when the sender, seen in the “From” field/header, is unknown or looks suspicious. For example:

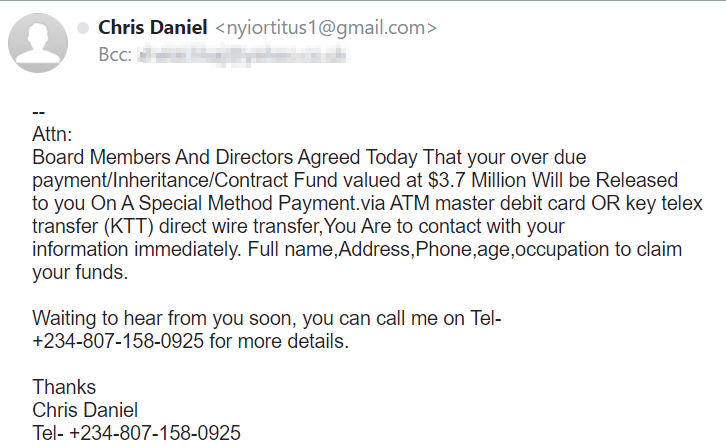

Example of a phishing email from an unknown sender

The first red flag in this email is the sender. Someone we do not know named “Chris Daniel” is emailing us from an unknown address. The first question the recipient has to ask is whether he knows the sender or not. Unlike phishing emails impersonating your bank, PayPal, or other financial institutions, these emails come from unknown people, promising a lot of money with an unreasonable motive (also known as the “Nigerian Prince Scheme”).

Moreover, notice how the recipient is in Bcc, and the body does not start with a concrete “Dear Recipient X”. This hints that this email was sent to many different people, hoping to hook as many victims as possible.

While grammar mistakes are hard to miss, it is also worth questioning the purpose of the email: what does the sender want from me? In this case, an unknown person is requesting your personal data, which none of us would give to a stranger.

EXAMPLE 2

Forged Sender (aka Email Impersonation)

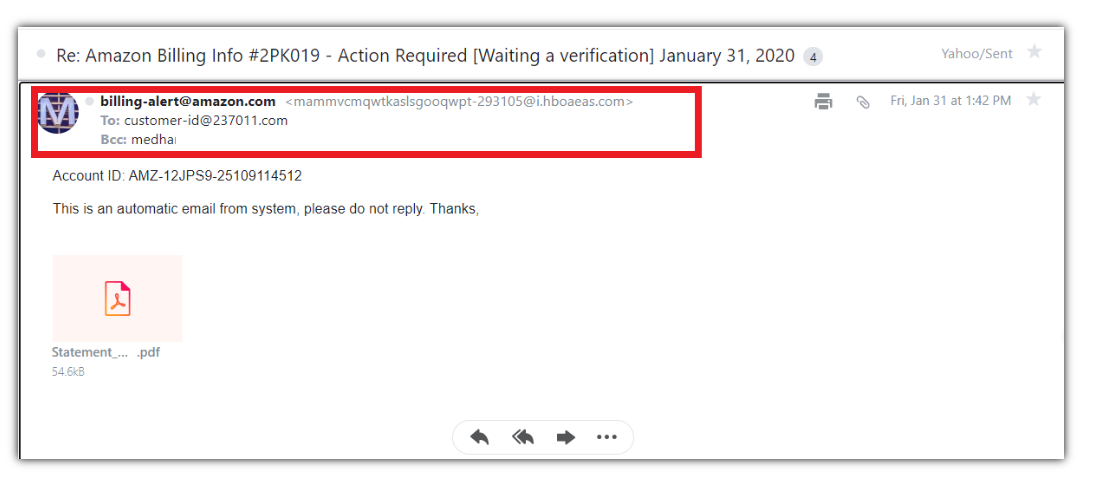

Another common type of phishing is when the attacker modifies the display name (see below in bold) to be an email address that does not match the full email address found in <> (the actual sender). In a standard email, both email addresses should match. Additionally, consider the domain name of the second email address in the “From:” header. It is doubtful that amazon.com also uses an esoteric domain such as i.hboaeas.com.

Mismatch between two email addresses on the “From” header. (Source)

The subject of the email is also worth studying. Most phishing emails try to create a sense of urgency to compel victims to do something before thinking through the potential consequences. In this case, the victim is asked to do something to ensure their purchase is processed.

Before opening the attachment, recipients should ask themselves:

- Did I order something recently? Was it from Amazon?

- It is not the first time I have ordered something on Amazon, why have I never received such an email before?

- If I have indeed ordered something, I can check the status of my order on Amazon’s website or mobile app. Does it show the same problem as this email? Does my account ID even match the one on this email?

While these types of emails come in different forms, impersonating various known entities, looking for inconsistencies in the “From:” field provides a clear red flag that this email should be considered suspicious. Questioning its content will help spot other inconsistencies that will turn the “maybe” into a “definitely”.

There is, however, a more advanced version of this forgery. It is important to emphasize that the “From” header can be completely manipulated by the attacker without causing any issues since this is not the actual header that indicates the email's sender. Another email header, “Mail From:”, will contain the sender's actual email address (see the SMTP RFC).

For example, an attacker could forge an email with:

From: alice@bank.com

Mail From: attacker@attacker.com

Note that only the “From:” header is shown to the recipient of the email, making it hard for the recipient to check the email's real sender without doing some more advanced inspection of the email header. Different email clients maintain the email headers in different places. For example, this article explains how to view all the email headers in Outlook. Though, it’s not realistic to expect recipients to know how to do this, or to do this every time they suspect an email may not be legit.

Note that the receiving email server will rename the “Mail From:” to “Return-Path:” and show the email address with which the sender presented himself to your email server. While looking at email headers is something “advanced” that most users cannot do, it is still worth including as an optional bonus section for advanced users. At the very least, everyone should know that even if the “From” header is a known sender, this does not mean the email is legitimate!

To add to the complexity, the attacker can decide to spoof the email's sender as an alternative to the phishing impersonation explained above. Attackers can do so by faking the “Mail From” email header, attempting to trick the email security tool (as well as the user). Therefore, it is crucial that you check and enforce that your email security tools are performing a Sender Policy Framework (SPF) check. An SPF check will detect the spoofing attempt by validating the sender’s email server IP against a list of the domain's allowed email server IPs. Upon failure, it is up to your organization to decide whether the email should be refused or marked as spam and delivered to the recipient. Alternatively, DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM) and Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance (DMARC) can be considered as well.

EXAMPLE 3

Compromised Sender

Instead of using unknown email addresses or forging sender email addresses, attackers could also compromise the computers or email addresses of people related to you. Then, the attackers can send phishing emails from this compromised email account as a reply to different recipients the victim was in touch with recently. Since the email comes from a trusted source and the subject makes sense (since it was a recent email exchange), it is often hard to distinguish it from a legitimate email.

For example, consider a car leasing company that has many clients. It is often the case that the company exchanges documents with the clients via email. If one of these clients is compromised by an attacker, the attacker could reply to one of the email conversations with a malicious attachment (e.g., as a reply to the company’s request to sign the leasing contract). Since this email and this attachment are expected from this client, the employee might open the malicious attachment without hesitation.

The good news is that, although the above scenario is challenging to recognize, in most cases, the attackers do not manually read previous emails and create a credible email. They use the same text content and send it as a reply to earlier emails to all entities the victim has exchanged emails with. In some cases, they reply to 1-year-old emails, raising questions for the recipient. Additionally, these emails do not contain a salutation, have content unrelated to what was discussed in that mail thread, and come unexpectedly. All these indicators can be used to identify potential phishing attacks.

EXAMPLE 4

Malicious Attachment

While URL-based phishing attacks remain the most common type, emails with malicious attachments can be equally or even more dangerous than URL-based attacks.

There are typically two types of malicious attachments: attachments containing phishing links and attachments containing malware.

Attachments containing phishing links

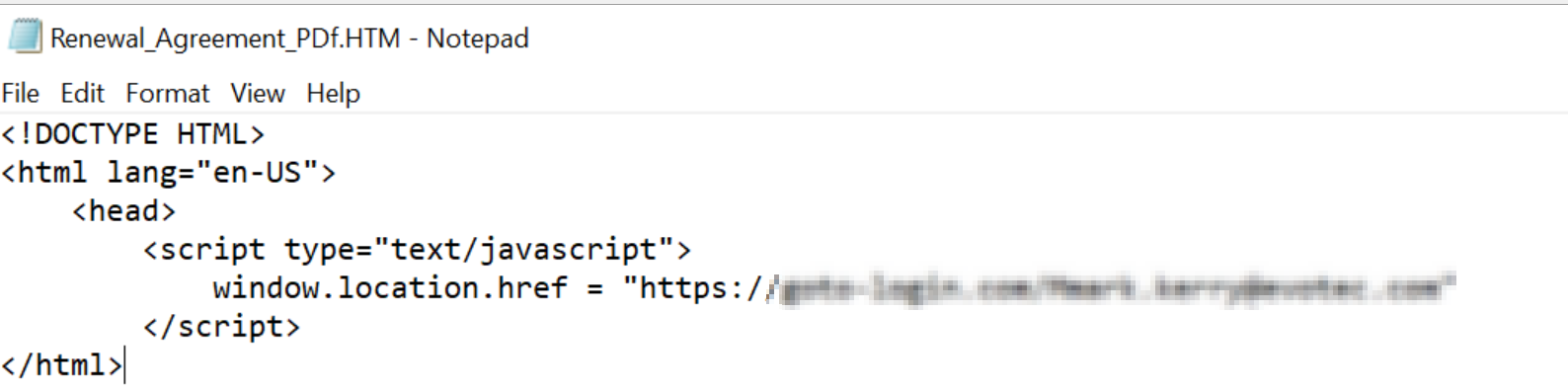

Example of malicious attachment containing a phishing URL.

Instead of including phishing URLs in the email body, which is often scanned by security tools, an attacker might place the phishing link in an attacked document. Different types of attachments, such as HTML, HTM, HTA, and PDF, can be used for this purpose. In the case of HTML-like attachments, double-clicking will open the browser, and the victim will land on the phishing site where they are prompted for credentials (for example).

These attachments are very short in content (as seen above) and do not require HTML or JavaScript knowledge to identify the malicious link. Therefore, security awareness training (SAT) lessons should emphasize that right-clicking and opening these attachments with Notepad.exe is far safer than double-clicking on the attachment. The recipient might quickly see a dubious URL, decide that the email is malicious, and stop interacting with it. Alternatively, recipients should be taught to escalate the suspicious email to their IT security department for review.

Attachments containing malware

Attackers can also send malicious attachments that contain malware to compromise the victim's computer with a virus or ransomware that, in some cases, can spread across a network. While most email servers are configured to block attachments with malicious extensions such as EXE, BAT, CMD, etc., not all attachments can be blocked without affecting business operations. For example, PDF is a common format for exchanging documents and ZIP is another common attachment for sending several files as a single attachment.

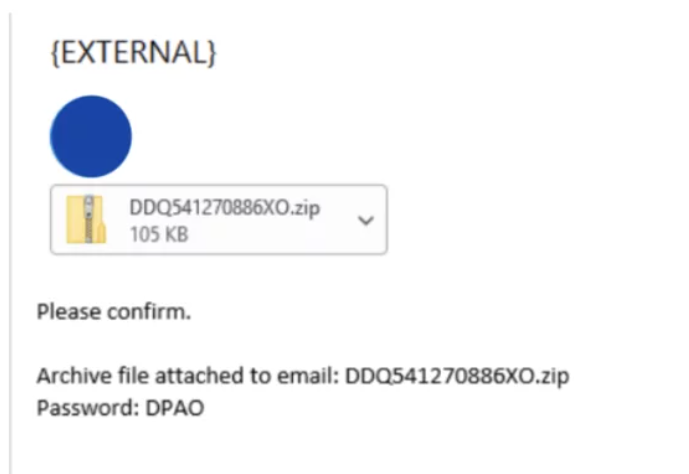

Attackers can leverage malicious forms of these attachments that are password-protected to prevent security tools from scanning their content before reaching the victim’s mailbox. The password is then provided in the email body, often with instructions on decrypting the attachment.

Example of phishing email with malicious password-protected zip archive. (Source)

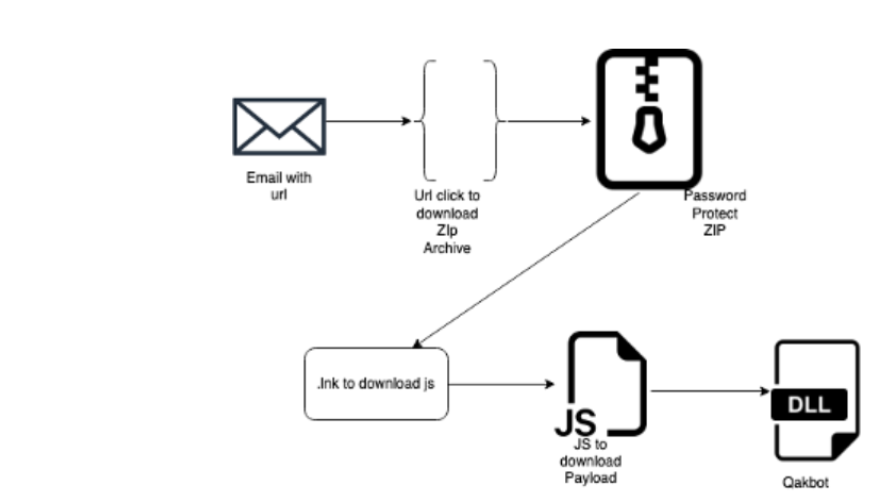

For example, a popular scheme is to send ZIP archives as attachments or links, leading to victims downloading a ZIP archive from the internet (e.g., from QakBot malware). These ZIP attachments are often encrypted, and the email provides the password.

QakBot mode of operation: password-protected ZIP archives. (Source)

Whenever employees receive password-protected attachments with the password in the same email, SAT should instruct employees to forward such emails to the security team for verification without interacting with the attachment. This is true for other types of suspicious attachments as well. If the attachment name is weird, unexpected, or opening it does “nothing,” employees should be instructed to always report such emails and their actions to the security team. SAT should also emphasize that falling victim and opening a malicious attachment is not subject to punishment and encourage the employees to report such events so that the security team can start remediation and incident response procedures before it is too late.

EXAMPLE 5

Malicious QR Code

Most phishing emails are URL- or attachment-based since they often aim to compromise the victim’s computer. However, there is an increase in the use of QR codes by attackers (aka Quishing). This has certain advantages for attackers since the QR codes are often not inspected by email security tools and such innovative methods might not be covered by traditional phishing simulation testing programs that do not keep up with the latest trends.

Example of phishing with QR codes. (Source)

Instead of scanning the QR code with a corporate or private mobile phone, employees should be instructed to use free online websites to upload a screenshot of the QR code and see where the QR leads without interacting with it directly.

EXAMPLE 6

Spear Phishing

While most phishing emails on the internet are opportunistic and are sent to thousands of recipients, hoping for as many victims as possible, spear phishing is different. Spear phishing is a more targeted approach that targets company VIPs, such as the C-level or people authorized to perform large transactions. With attackers now leveraging AI tools like ChatGPT to craft even more convincing messages, spear phishing emails have become increasingly sophisticated, often featuring well-researched details about the victim (e.g., gleaned from their social media presence). It's crucial to double-check the sender and look out for any typos in the sender's domain name (see typosquatting attack). If the sender is forged (using any of the methods mentioned above), that's a huge red flag, and you should avoid sharing any transaction details or sensitive information.

Always apply the 4-eye principle for large transactions and instruct employees to always ask at least one other employee to review the request before performing critical actions like approving large transactions. Since attackers often impersonate C-level management, instruct employees to try to reach out to them internally by using their internal email address or phone number and ask if the request is really coming from them.

EXAMPLE 7

Smishing

Smishing or SMS-based phishing is another form of phishing that tries to deceive the victim by creating credible SMS messages.

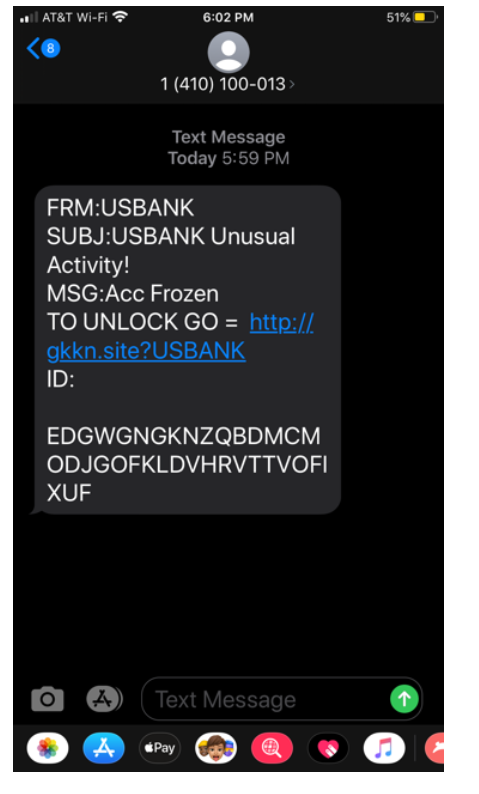

An example of smishing. (Source)

Take the above example above. Although the text content is really dubious and no bank would send such a message, look at the link. It leads to a questionable website with nothing to do with “USBANK”. In such cases, employees should be instructed to either:

- Hover over the link and see a preview of the website the URL leads to (provided by most modern phones)

or

- Copy the URL and, like URL-based email phishing, open the link in a free online sandbox such as urlscan.io. This way, the recipient can check the actual destination and purpose of the URL without clicking on it.

EXAMPLE 8

Vishing

Like smishing, attackers use vishing (voice phishing) to deceive victims and steal personal or sensitive information, often impersonating managers or members of the police force. Sometimes the vishing message is a coordinated step to reinforce a BEC or spear phishing email already sent to the recipient.

Three common indicators of a vishing attack include:

- The phone number making the call. If the prefix belongs to some random country in Africa or a region your company has no presence, this is the first red flag to treat the call as suspicious.

- The language being spoken, accent, and mistakes during the call. These are most likely indicators that the caller is from a different country, company, or region than you are.

- The information requested. Suppose personal data or information about the company, its structure, or other internal information is requested. In that case, employees should be instructed to interrupt their conversation and request that the caller send an official email so that his request can be processed and that no sensitive information will be provided in a phone call. At this point, most callers will hang up, indicating that the call was probably a vishing attempt.

Best practice: Keep SAT content and phishing examples up-to-date

We only covered the main types of phishing. However, this list is not exhaustive and changes from time to time as attackers get more and more innovative. Staying up-to-date with the latest techniques and phishing examples can be challenging, particularly for organizations whose core competencies aren’t in cybersecurity. To ensure that your organization’s SAT content is current and effective, consider using IRONSCALES' purpose-built security awareness training products that include hyper-personalized phishing simulation.

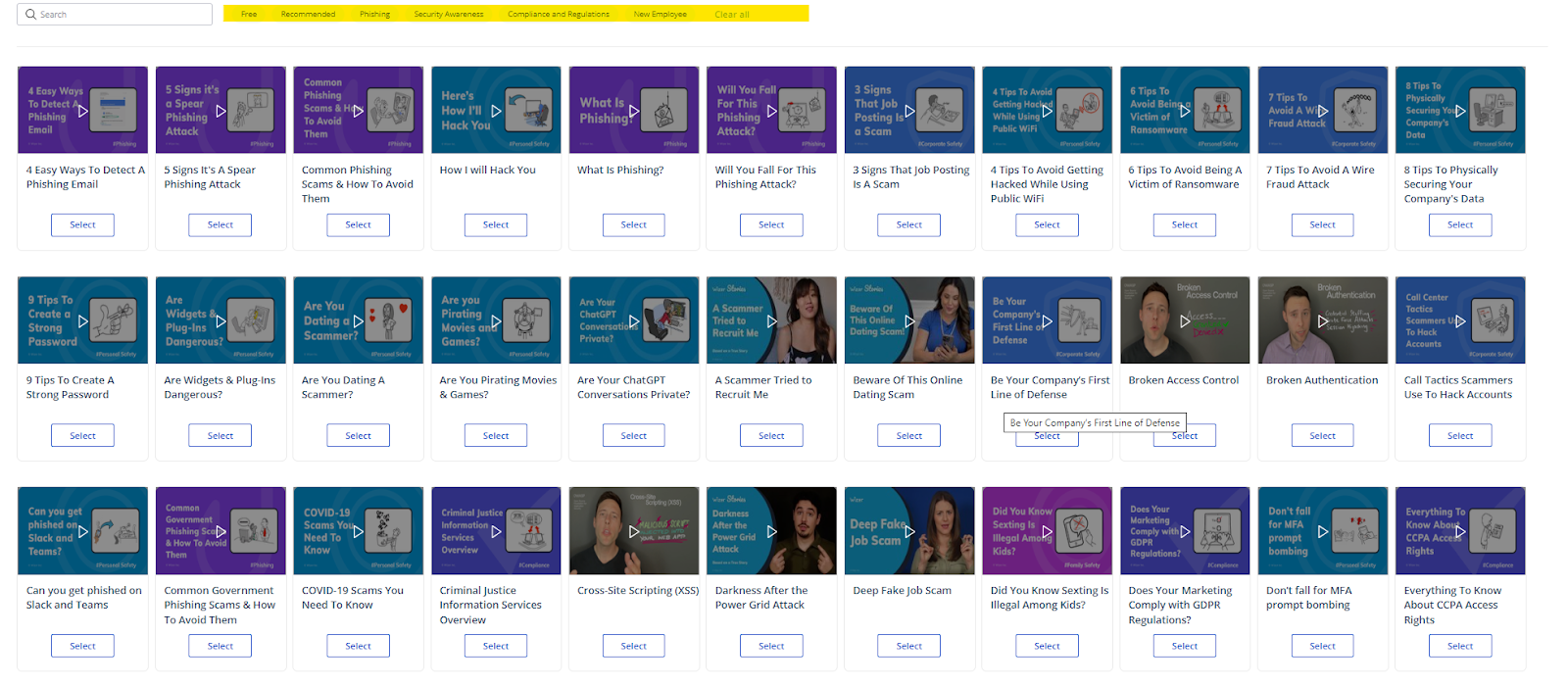

IronScales variety of training material, covering different phishing topics and examples.

Conclusion

For SAT to be effective, it must contain meaningful content and concrete phishing examples. Security awareness training covering this article's eight examples is an excellent foundation. While there are other forms of phishing, the risk of falling victim to other “exotic” variations also decreases by familiarizing employees with the primary flavors of phishing.

/Concentrix%20Case%20Study.webp?width=568&height=326&name=Concentrix%20Case%20Study.webp)